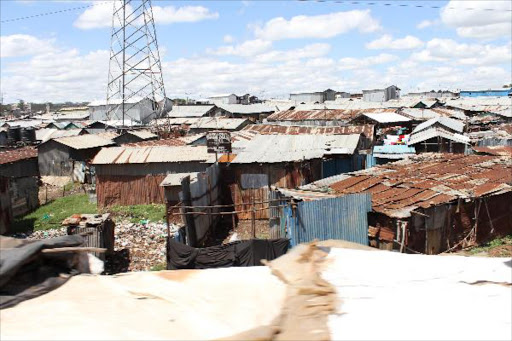

Deep inside Nairobi’s Mukuru Kwa Njenga slums, the right turn indicated on Google Maps is a dead end, a dingy lane with rocks on one side, stagnant water on the other.

People jumped one by one, from one stone to another, splashing dirty water as they approached the single-lane tarmac.

They looked amused we thought a car could pass. No one said a word until we asked for directions.

The first person we asked knew the house of Mzee Njenga Mwenda Kariuki, for whom the slum was named.

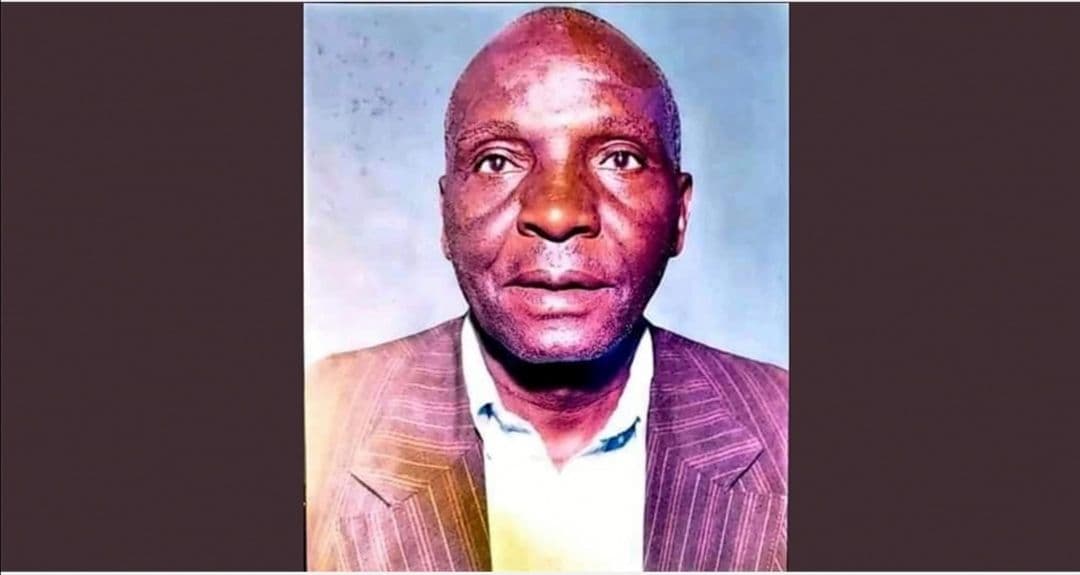

Njenga died on February 8 in his car on the way to the hospital. He had suffered chest complications for more than 10 years. He was 89.

Mzee was a slumlord in the best sense of the word. He could have lived anywhere but chose his slum where he was respected and beloved for his helping hand.

“We hope the body will be brought here so we can pay our final respects. He was kind,” the man told us.

He will be buried on Wednesday at Lang’ata Cemetery.

We passed corrugated iron sheet shacks, piles of garbage and an open, foul-smelling sewer. That’s what passed for a children’s playground.

At Njenga’s house, it was obvious this was no ordinary slum house.

Past the blue gate stands a stone-walled house. The front yard is large enough to hold a medium sized-chicken coop, a goat shed and leave space for three small tents for mourners.

Green flowers hung neatly in the foyer leading to a tidy living room.

Political careers were born and destroyed in this room. To those he believed in, Njenga gave his blessings. To those he doubted, he did not mince words but advised caution.

“I barely know anything from my father’s past, my elder sister can tell you more,” Muthoni Njenga, one of Mzee’s three daughters, said.

Muthoni, 38, did tell us her father had seven children with his first wife, then separated and remarried.

“In total we were 13 children and we all grew up together here,” she said.

Nancy Wanjiru, 49, Njenga’s second child, said their father had moved to Nairobi from Limuru in 1956 at age 22, first landing in Kamiti.

This was during the Lari Massacre when many Mau Mau fighters were killed after they refused to leave their land and allow Europeans to settle there. They were told to move to inferior land in Lari.

By 1952 in the Mau Mau uprising, fighters were attacking political opponents, raiding white settlers’ farms and destroying livestock. They took the oath.

From October 1952 to 1960, the British declared a state of emergency and moved army reinforcements into Kenya. Tens of thousands were killed.

It was during that period that Njenga moved to Nairobi, first living in the streets before making friends who took him in.

After working for the Kenya Planters Corporation Union, Njenga quit to become an entrepreneur.

“Mukuru Kwa Njenga was bare land full of rocks. Many people of Asian descent had quarries where they employed locals. That is where Njenga saw an opportunity and began selling pork to workers in an open restaurant,” Wanjiru said.

Njenga later started selling chang’aa to the labourers after work.

He was living in a makeshift house like most workers. They could not build permanent houses because the land belonged to the government.

“City askaris in khaki shorts were ruthless. They would torch their houses and destroy their things whenever they raided,” his daughter said

Wanjiru said the workers had nowhere to go. Their employers had fled leaving them with nothing.

“The cat-and-mouse game with the askaris continued until one day, the Embakasi village chief approached my father, asking him to start a village here,” she recounted.

Njenga expanded his business, opening a bigger restaurant and a bar. As his business grew, so did his reputation.

Many people went to his bar, which they called Kwa Njenga, for entertainment and chitchat.

“Mukuru is a Kikuyu word for valley. After the quarries were dug, they left holes the locals called mukuru. To identify this specific mukuru, locals added Kwa Njenga. That was the birth of the name of the estate, Mukuru Kwa Njenga,” Wanjiru explained.

More people visited Kwa Njenga and some drove their cars, prompting Njega to start selling fuel from tanks. “This grew his name further,” Wanjiru said.

Mukuru Kwa Njenga started with fewer than 4,000 people from across the railway to Njenga’s residence. Today, the slum has expanded to 113,000 people in eight zones.

Across the railway line is Mukuru Kwa Ruben, named after a white settler. Not far away is Mukuru Kayaba, said to have been named after a kei apple fence that marked its border.

Kwa Manyanga bar and restaurant across the road from Njenga’s residence is still operating. Now it sells beer and liquor, not illicit brew. Next to it is a small house that the residents said was his favourite spot.

“My father woke up at 4am daily and turned on the radio that he preferred to television. At 5am he got out of bed, showered and put on his suit,” his 49-year-old daughter said.

Njenga always wore a suit, a clean and pressed shirt and polished shoes, a habit from his colonial schooling.

Njenga went to Loreto Mission, an approved school where young adults were forced to study. He dropped out, his daughters don’t know why.

“Even though he wasn’t properly educated himself, my father, an utter disciplinarian, ensured we all went to school. He would even call our school asking them not to allow us to come home for half-term. We never lacked school fees,” Wanjiru said.

Njenga never returned to the countryside after he left, until his last days on earth.

A week before he died, Njenga invited his daughter Wanjiru for lunch at his bar.

“He inquired about all his children, seeking every detail. When I asked why he was so concerned with all of our affairs, he said I was easy to talk to and he wanted to know his children’s welfare,” she recounted.

“That day, he insisted on eating roast meat and had his pocket knife handy to help with that.”

Mzee asked her to accompany him to the village after a long time when he visited his niece. After that visit, his chest problems worsened.

“After about four days, his condition had not improved and he asked to be taken to Mbagathi Hospital,” she narrated, her face dimming.

Njenga had bought a car two months before and said it would be used to transport him to the hospital whenever necessary.

“On his way to Mbagathi, on February 8, around 5pm, in the company of his son, Mzee Njenga took his final breath,” she said.

Njenga Mwenda Kariuki leaves behind 13 children, numerous grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

At Mukuru Kwa Njenga, the residents hoped the family would go against its traditions and allow them pay their last respects to the founder of their homes.

Kennedy Ang’ueth, a village elder, said he had come to ask the family to bring Mzee Njenga’s body to the estate for viewing before burial in Lang’ata, according to his wishes.

“Mzee was not greedy. He gave many people here land. He was friendly and always listening. Also, he did not discriminate on tribal or age grounds. He accommodated everyone and gave advice when required,” he said

“Land grabbers from different places came and started to grab then sell to wananchi, and it wasn’t his wish. If he was greedy, he could have owned the whole of Kwa Njenga. Nobody could have stopped him.”

The Njengas admit their father’s name has opened some doors for them, though they wish authorities would ensure a good supply of water, electricity and other amenities.

“We lack infrastructure. No water, no access roads or drainage systems. That’s what we wish the government could build for us,” Wanjiru said.

Mukuru residents particularly want titles to the land.

A January 2015 memorandum to President Uhuru Kenyatta, signed by 27 Mukuru Kwa Njenga residents, states Mzee Njenga was the chairman of the founding members of the slum, at least 15.

“He dealt with conflict resolutions and such. When populations shot up, he and the area chief could show someone where to put up a structure,” Wanjiru.

As a family, Wanjiru said she hope to continue Mzee Njenga’s legacy through helping other people.

“I am a community health volunteer here, I also handle gender issues and I am a village elder. I know my siblings want the same too,” she said.

Via the star